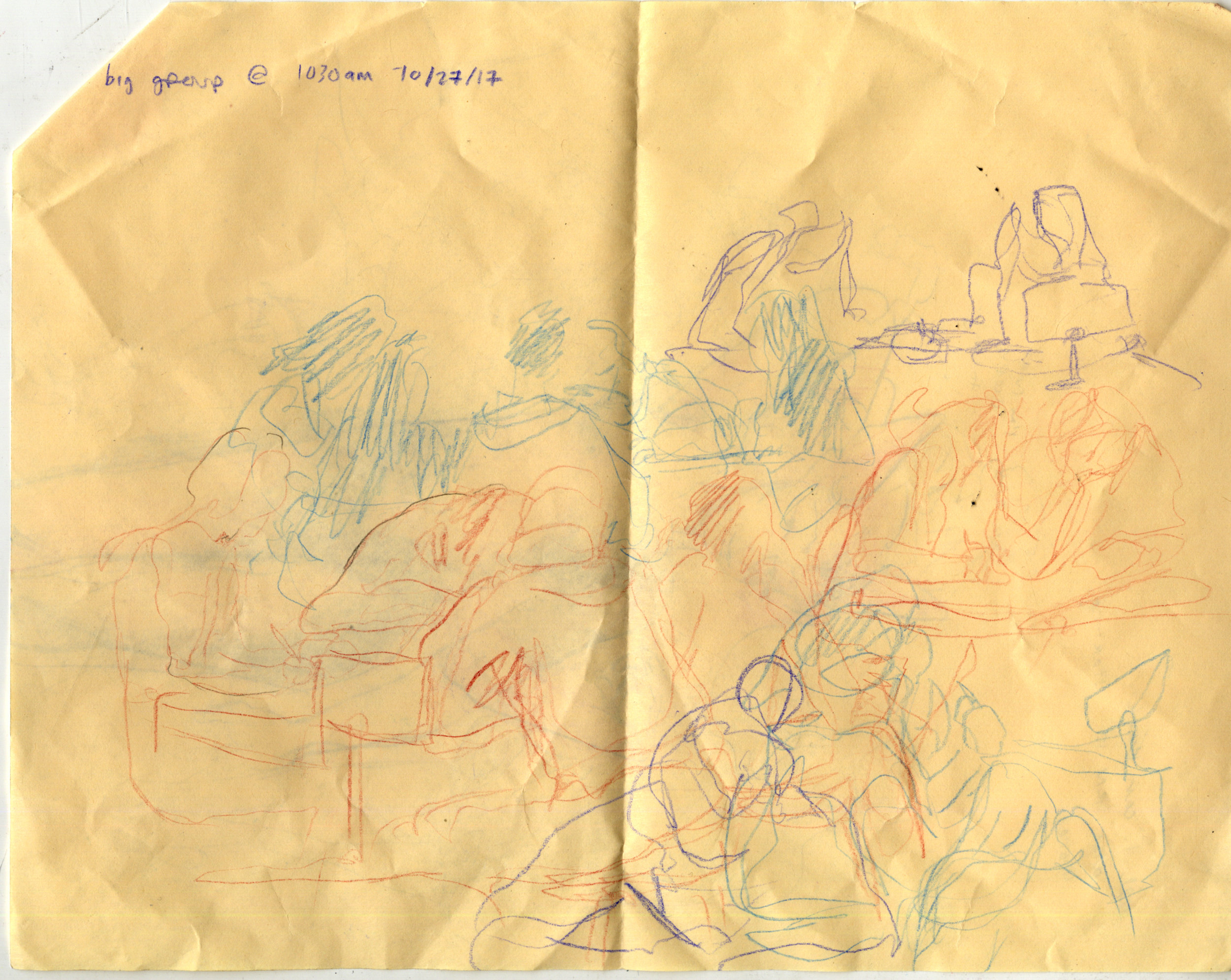

drawing on the museum: notes, observations, and inquires from my time at the risd museum's out of line drawing exhibition

the space, october 26th 2017

the space in november 2017, with my initial attempts at invitations (tape on the floor + the sign)

i’d like to begin by acknowledging the land in which the museum is located is the traditional territory of the narragansett peoples.

i'd also like to acknowledge that museums are colonialist institutions, and that under capitalism benefit from serving the interests of the upper/middle classes.

maybe it seems a little strong to frame what are essentially drabbles on my experiences encouraging people to draw like this. but we live in times of political upheaval and changing paradigms. when people walk into a museum, whether as a visitor or an employee, whatever they carry with them as a member of society does not cease to exist. conversations about the roles museums play in communities and conversations about navigating - and how to make right - the history of art museums as white supremacist institutions need to be happening and need to be ongoing.

i do not speak for the RISD museum. these observations are my own.

the setup

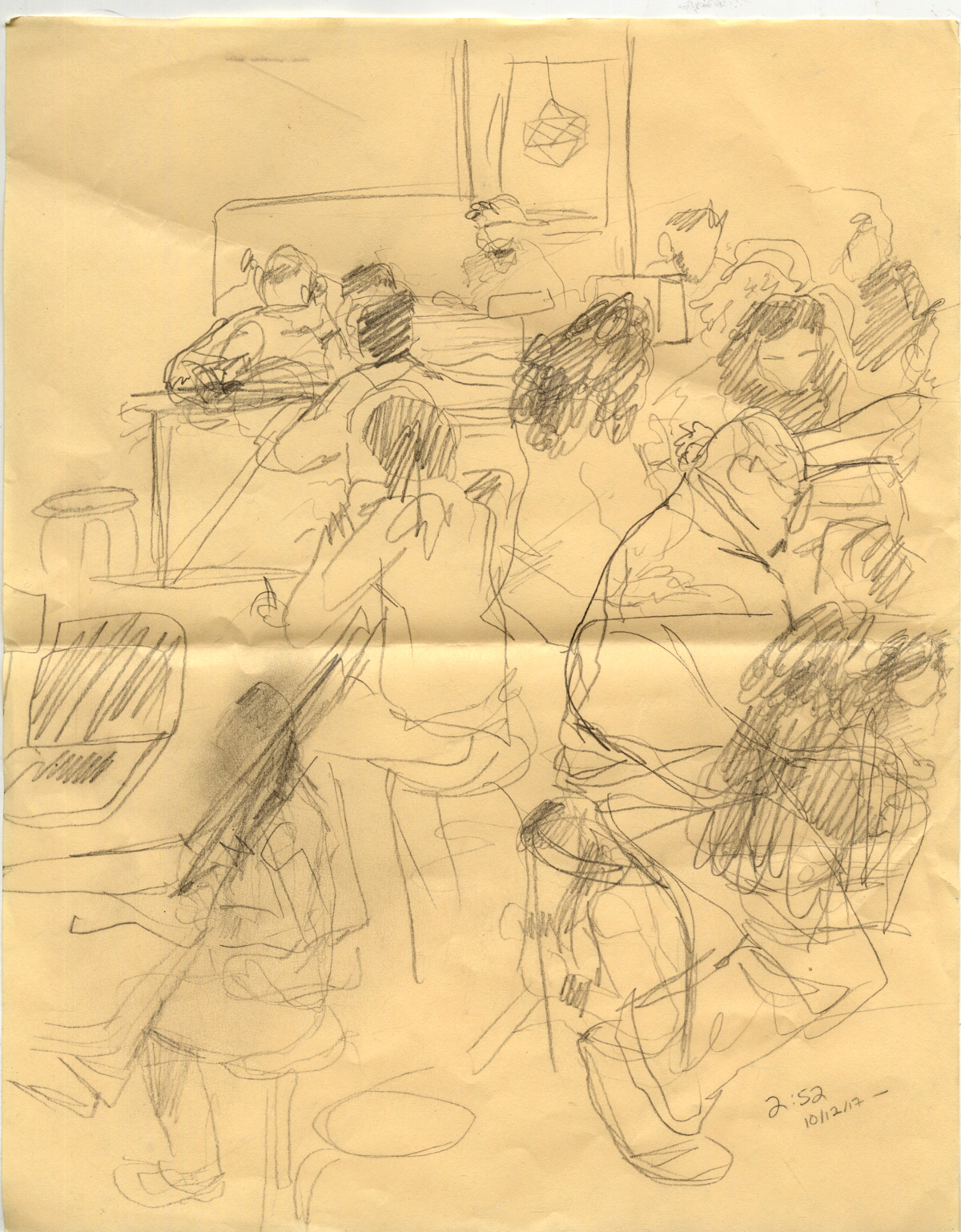

the space was located on the 3rd floor of the chace gallery beside the special exhibition and ran from october 6th, 2017 to january 7th, 2018. it occupied the liminal space between the elevators and the bridge to the benefit st building, so that in order to visit both buildings every museum visitor must pass by us. the room itself was delineated from this path via a set of wood and acrylic cabinets which house a number of objects from the RISD nature lab. within the space there were eight tables and forty stools arranged on a carpeted area; another wood cabinet containing a number of art supplies (white, black, cream and kraft papers, pencils, colored pencils, acrylic risers, binder clips, chipboard, and so forth); a television display that plays a movie illustrating the drawing prompts; a series of plastic potted plants.

within the space, the other gallery host and i were given a fair amount of freedom to arrange and rearrange at will. this primarily involves moving the tables around as well as controlling what and how much of the visitor’s art is hung on our walls. we were also able to take out objects from the nature lab cabinets for guests and/or arrange our own displays on the tables for visitors. we also had the freedom to create our own daily activities, prompts and so forth which i will discuss in greater detail in a bit.

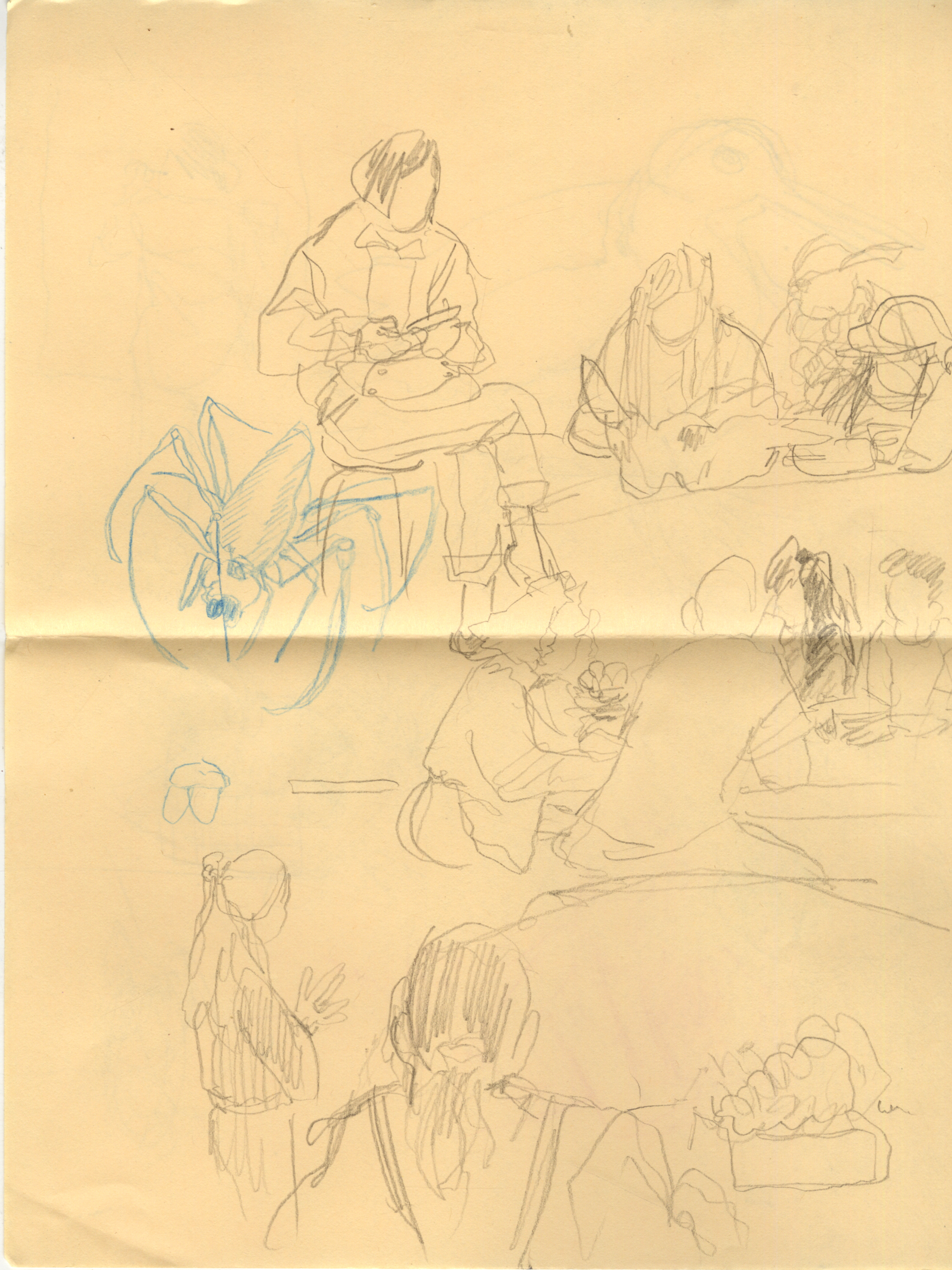

during my time in the space i developed a set of behaviors for myself and how i interacted with the museum visitors. my primary focus was on ensuring that the space felt open & welcoming for anyone, regardless of whether or not they self-identified as artistic or not. the language we use around art making is particularly important and so i sought to find ways to invite visitors into the space without placing a burden of expectation on them.

for a lot of people, art making is itself a traumatic act. for a great many others, it is simply seen as something frivolous or unnecessary, or even “just for children”. even in the risd museum, where many of the visitors were self-identified artists or connected to the arts in some way already, that hesitation was something i ran into often. creating ways of engaging with these visitors so i could gently challenge or encourage their self perceptions became a focus of mine — through suggesting specific, low pressure drawing prompts, giving supportive feedback, or encouraging play through activities such as exquisite corpse. the best moments were those few times someone would tell me they’d just made their “first” drawing, or that they’d abandoned drawing when they were younger but wanted to pick it up again after playing in the space. for me the goal was not to try and educate visitors on how to draw but to make the case that drawing could be something they did at all, whether seriously or not.

i always thanked people for drawing as they left, whether they kept the drawing, hung it up, or just left it behind on a table. even if they’d just sat around and scribbled for a couple of minutes, i thanked them — because how often do you get thanked for engaging in something that produces no material benefit?

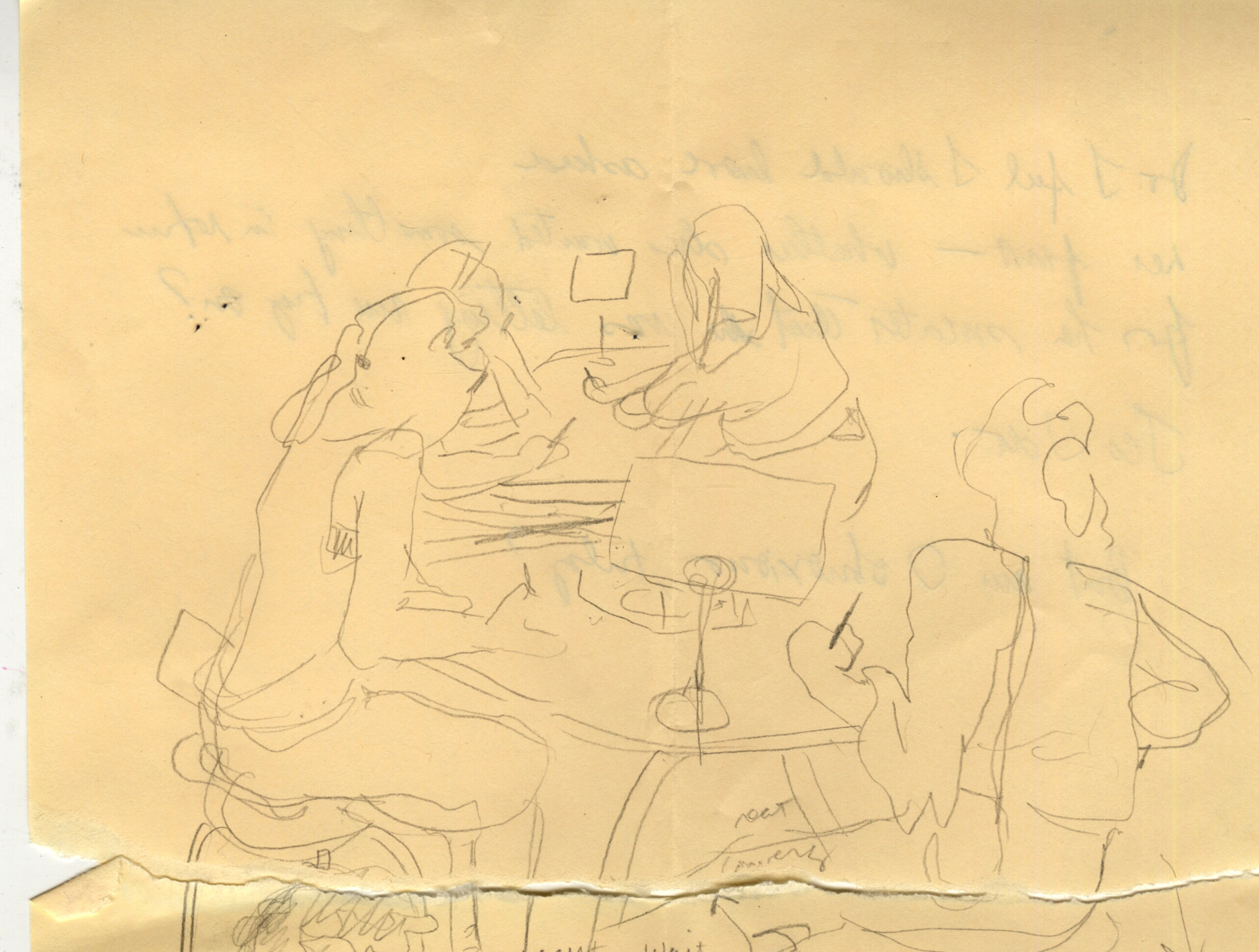

comic from the space, november ish

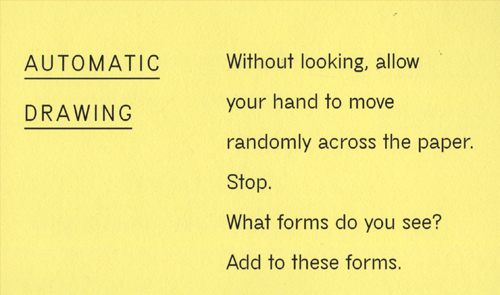

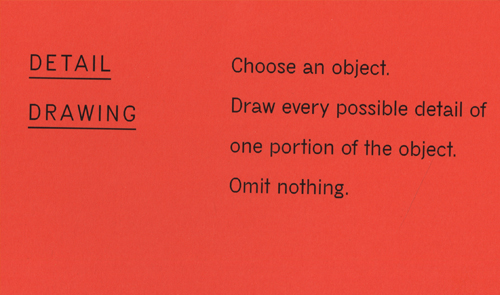

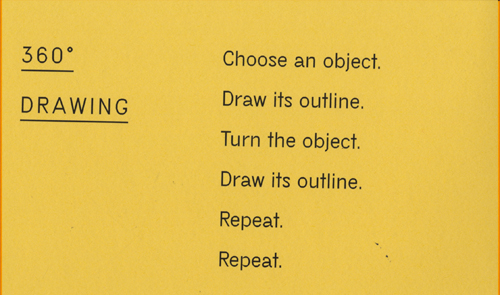

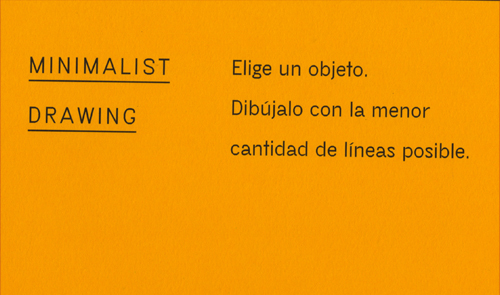

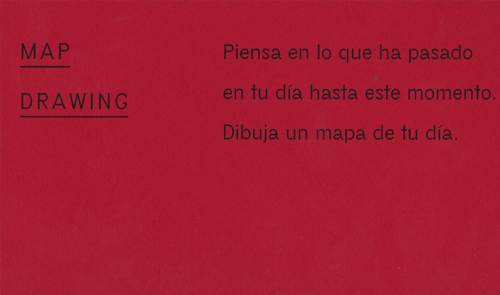

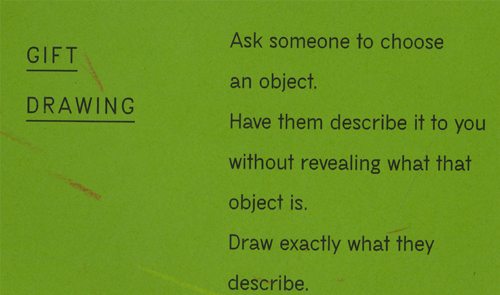

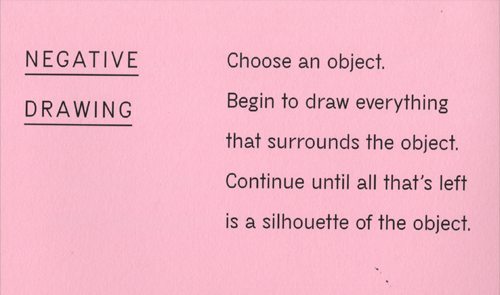

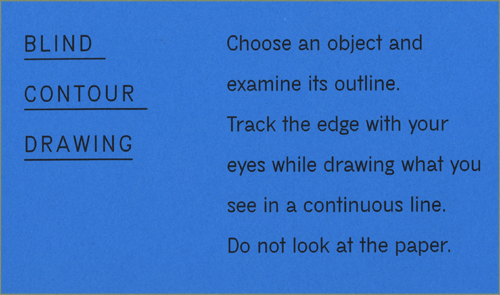

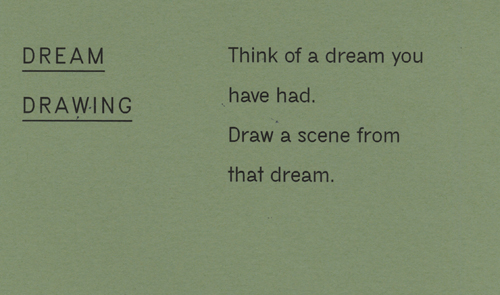

drawing prompts, courtesy of the risd museum

once a visitor told me, "your pencils look uninviting." i asked him to clarify, but he just shrugged and drew for a bit.

i wonder still what was uninviting about the pencils to him. i liked the pencils, and the intentional lack of erasers, because anyone can get ahold of a pencil and draw something.

early one november morning i found myself in conversation with one of the museum's education staff. one of the things about the space i figured out immediately was that, to the average person, it looked off limits -- most people walking by would ask if it was for a class/for students or part of a performance rather than for them. given the strange liminal nature of the space that wasn’t very surprising but the question i became slightly obsessed with was: how do you get people to realise they’re allowed to just come in?

it’s not as easy as it sounds on paper. i was pushing back on these ideas about what a museum is, or at least what the risd museum is. there was a write up on the wall about the space, but placed as it was next to the opening of the exhibit, i got the impression many people failed to make the connection -- it doesn’t help that it was written in that peculiar language of “art speak”, which flows beautifully off the tongue but often fails to make things clear to the uninitiated.

i’d only been there a month and i was still dealing with my own anxiety about stepping on toes, unsure exactly how to define myself (educator? part time employee? etc), but i felt safe enough with the education team to raise the issue. i already had some ideas, but i asked, “what do you think we could do to make it more inviting?”

“try tape on the floor,” she suggested -- which i’d been nervous to do in case it made things difficult for the cleaning staff. but i went upstairs and made my first attempt at a bigger, simple sign (“WELCOME! COME IN AND DRAW” it said in slightly crooked tape letters), and then set about to putting down a bunch of arrows in tape and more “WELCOME! COME DRAW”s.

museum comix #1 - e jackson, 2018

from there i started experimenting with other signs and signals. it’s hard to qualify, of course, if all of my attempts made significant changes (correlation and causation, after all). but after they went up the questions shifted from “what is this/is this for students” to “can we draw here” -- still encountering hesitancy, but hesitancy that seemed rooted in that challenge to what you’re allowed to do in a museum versus what the space actually was.

my next logical step, then, was interventions into the space. from the jump i’d definitely envisioned playing with the parameters of what activities visitors could do. the full extent of that never got completely realised due to constraints with my time in the space and the patterns of visitors per day, but i did get to pull off some things. i developed a habit of covering the tables with brown butcher paper after we did so for a highschool event. the paper covered tables looked much more playful (to me anyway) and invited a less serious mode of drawing - namely, that people could stop by and doodle on the table itself, rather than commit to the act of drawing on paper.

from there it became a matter of seeing how far away i could push from the slightly sanitized aesthetic of the museum into a more warm/open workspace environment. at the height of this i pushed a bunch of the tables together into a ‘family’ style grouping, covered them, and then dumped the pencils all over the table, removing as much of the organization of the space as i could. my goal was to make the space look visually accessible and playful -- by engaging people with drawing as play rather than drawing as skill it was easier to break through the walls people built against art-making.

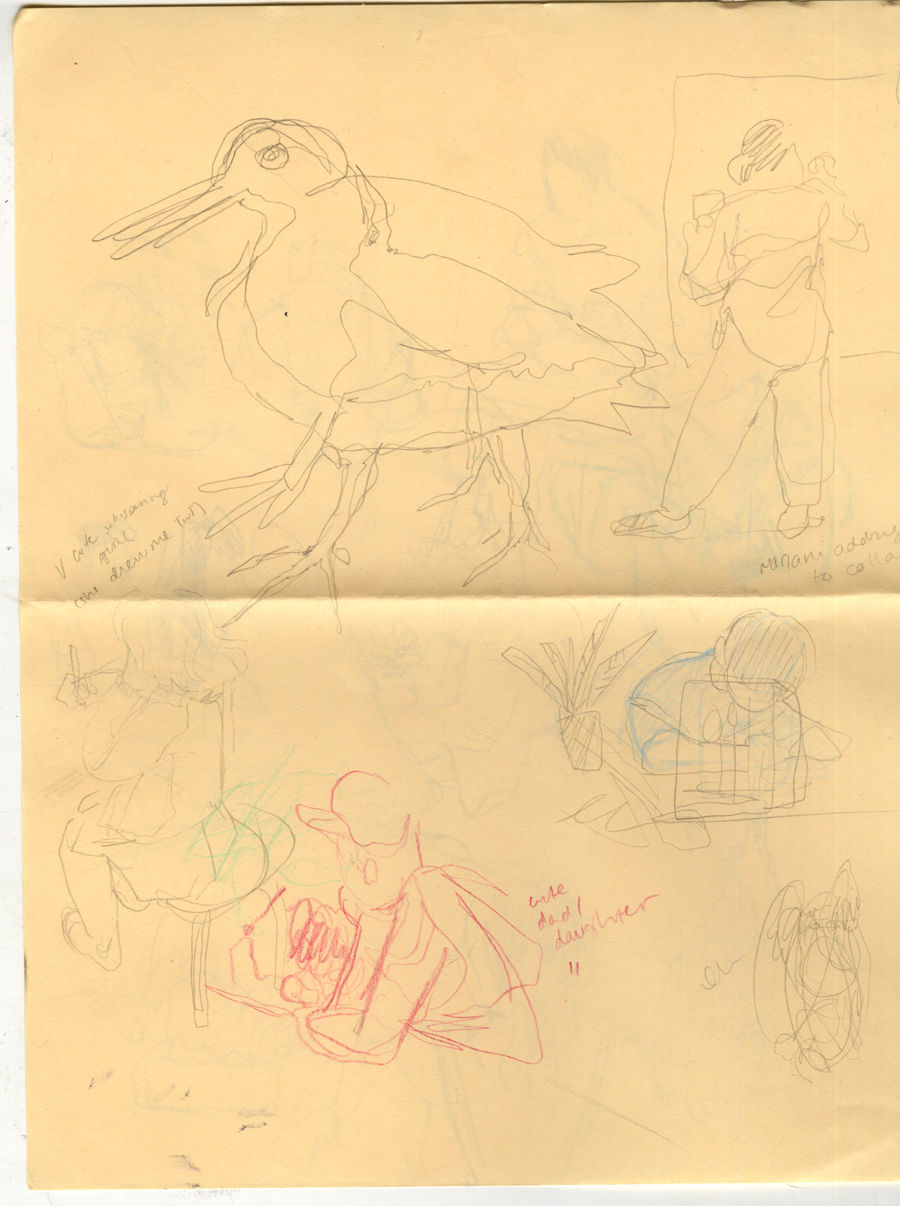

most frequently i tried to take a hands-off approach with visitor interactions, but i did have the opportunity to run some small scale workshops/activities in the space. the first i tried in october, turning to an old favorite of mine: exquisite corpses, the kind where you fold a slip of paper in third and have each person draw a different part of the body without looking at the other parts. i wrote the instructions and set it out on a table with some prepared paper, and then spent the day approaching people and asking them to contribute a head, a torso, or legs. my hope was that because it was a game rather than a serious task, and because it required minimal commitment, i could get some reluctant folks in on it.

there were definitely people who did not feel comfortable with even that small amount of drawing, but i was able to get some people who definitely balked at the idea of drawing a whole drawing of their own. and interestingly, once i had a few completed, people began to pick up the task without my prompting, which was exciting to watch unfold.

other small experiments followed: drawing on the tables (noted above, successful), drawing on the walls (unsuccessful -- i wonder if it had to do with the fact that finished drawings were hung on the walls as well, creating a sort of “don’t touch” vibe?), big collaborative drawings (mixed success -- the most successful one was actually begun by my co-host on his first day). once i covered the tables in paper, took away the drawing papers, and only placed out the automatic drawing prompts to see if i could get some big, continuous automatic drawing happening -- with mixed success (still fun, in my opinion). of course i’m only commenting on the activities i personally ran here -- throughout the run of the show the museum organized weekly lunchtime artist workshops featuring local artists, and the museum’s open studio & third thursday events also occurred in the space, all really wonderful things.

i ran two of the weekly lunchtime workshops. the first was because the artist fell ill and i gladly stepped in to substitute: we did jam comics. i had everyone present fold one of our papers into 8ths, creating an 8 panel sheet of paper, and asked them to fill the first panel in based on our “draw a dream you’ve had” prompt. it was my first time running a directed workshop -- since i was filling in, i wasn’t exactly what the visitors had expected, but i was glad to get the opportunity to bring something more casual to the space.

my actual scheduled workshop was met with a blizzard and then a lighter snowstorm -- but i had the advantage of working there, so i just made it an all day event and let folks trickle in when they came by. for this one i focused on minizines -- zines created from a single sheet of paper, folded in such a way as to have 8-10 pages. my goal was to teach a skill that could be easily recreated again, since all that’s needed is a sheet of paper, a pencil, and a way to cut the paper (in a pinch, tearing works fine). i also wanted to be able to have everyone make something tangible they could carry home that didn’t have to be completed in the workshop space. i didn’t have any specific goals for what the actual zines would contain, so i provided a list of prompts and brought in some stickers and fancy paper.

i was a little worried people would need more direction, but once they got the hang of the paper folding, they took off with little need for prompting on my end. i was fortunate enough to repeat this workshop at a third thursday and i saw the same results -- it’s really fantastic to witness the range of creativity that people have, and one of the things i love about zines is that they have room for a more chaotic, abstract, disorganized presentation of information or ideas.

zine-ing in the museum is something i hope to revisit on a bigger scale some day. zines, along with comics, are possibly the most democratic and accessible art form -- paper and pencil is all you need to make them, and they’re good tools for processing thoughts, memories and feelings. what better object to make in a museum, where you probably have some feelings to process about the art you’re seeing?

“The Arts can be alienating for a lot of people. Art’s function as capital can create social order and class divisions, designate certain types of media as highbrow or lowbrow, and as a result many people believe art is outside their realm of possibility. The average adult is nervous to pick up a pencil and draw. Children can oppress their own creativity. People can feel like they don’t have the skills or the knowledge to be an artist. People think they don’t know what real art is, that their creative thoughts and beliefs don’t count."

Cathy G. Johnson, Developing the Cartooning Mind: The History, Theory, Benefit and Practice of Comic Books in Visual Arts Education

throughout this "zine" i’ve alluded to the anxiety a self-identified “non artist” might feel about the act of drawing. and i don’t mean to suggest that self-identified “artists” don’t experience anxiety re: art-making -- although i consider myself as an artist very fortunate to have been positively reinforced in my art-making for the most part throughout my life, i recognize that for many artists that’s not the case, and even the most outwardly successful artist can still struggle with feeling connected to the arts.

but the fact remains that art-making is an intensely intimate act, and one that is associated with trauma for a lot of people. many people stop or become discouraged by drawing as preadolesences and disparaging remarks about their drawings from teachers and parents can and do impact a child’s feelings about art well into their adulthood.* while working at the museum i’d hear the same hesitancy and dismissal from visitors: “i can’t draw”, “i’m no artist”, “it brings up bad memories”, etc. once an older women explained to me that art was “the only class [she’d] ever failed,” and that she was “so humiliated” she never tried to draw again.

it makes sense that these discouragements have such a strong impact on us as children and as adults. art-making is a act of expression; for children, considered one of the most important acts of expression*. any act of expression makes us vulnerable, and “after all, wanting to be understood is a basic need — an affirmation of the humanity you share with everyone around you.”* when that vulnerability is met with disapproval, discouragement or even scorn, it can be traumatizing, permanently damaging the relationship someone has with art and art-making. people become afraid of not being good enough or of being judged by others and consequently distance themselves from art, when art is a fundamental part of human existence.

so how do you reconnect the dots? the obvious answer is of course to challenge the system of early arts education, so that art doesn’t become disconnected from children’s lives in the way it frequently does during preadolescence, and to find ways to uplift children - especially children of marginalized experiences - in their art-making. but this answer doesn’t account for those already past the critical period, older children, teenagers and adults who have been discouraged or prevented from connecting with the arts.

there is no one quick fix for dealing with cultural trauma around the arts. it begins with reckoning with the systems of colonialism, sexism and white supremacy that lay in the foundations of the art world. it begins with examining honestly the critical theories of art history, with re-evaluating the purpose of the canon and the “western” cultural hegemony. it begins with challenging the devaluation of arts in public education to an increasingly inaccessible privileged “elite” class of people, and treating art-making -- and art education -- like a frivolity, rather than a basic human right. it means no longer idolizing individual artists as mystic geniuses, whose talents are mysterious god-given gifts no average person could hope to emulate.

it means making museums belong to the community -- giving ownership of art back to people instead of privileged authorities. the out of line drawing space is one way to start these conversations. its existence began to break down the divide between what’s hanging on the wall & who comes to see it, and challenges institutional perceptions of what an art museum’s function is. although limited, it was a step in the right direction, and hopefully a concept that the risd museum and other museums will return to.

exquisite corpses by museum visitors

"jam comix" from lunchtime workshop, dec 2017

drawings by visitors hung on the gallery walls

art-making is a fundamental human right.

my favorite day to work at the museum was sundays, which are free to the public. the difference between the monday-saturday crowd and the sunday crowd was noticeable: busier, because it’s a weekend and a free day, of course, and also significantly more diverse across all categories.

museums are not accessible venues. some are, or make concerted efforts to be (the risd museum does also offers free admission during their third thursday events, free admission to youth under 18, and free admission to self-identified artists with their artists membership -- it’s a start), but the history of museums is tied to their cultural legacy as colonial makers of meaning. from “museums in the colonial horizon of modernity” by walter mignolo:

“because museums emerged during the renaissance, they have also been linked to the logic of coloniality (the need to convert and civilize the inhabitants of the planet that were still outside history, the barbarians and primitives). consequently, museums followed two complementary directions in the accumulation of meaning: one type of museum documented and consolidated the genealogy of european history. art museums were and still are the epitome of this direction. the second type was the ethnographic and natural museum, which documented “other cultures”, including their art.”

the impact of these origins can still be seen today, from the way “western” and “non-western” are treated as viable divisions in understanding art, to how contemporary artistic standards are still set by eurocentric parameters. the art historical canon, historically reinforced through museums and other institutes of art, has from the start been designed to situate the artist-genius as a white upper-class man, so that marginalized groups within the “west” have also been systematically excluded from our understanding of art history.

so consider for most people, the works of art upheld by institutions of art are not as “universal” as we would like to think of them as. people have been discouraged from making art themselves, have not been given the tools to feel empowered by art-making, and have been systematically excluded from visual culture, denied even the dignity of reasonable representation. why on earth would they feel like art benefits them in any way?

within our society we either dismiss art-making as something frivolous, for children, or we treat it as something only “geniuses” should be allowed to do. we encourage the “genius” idea by carefully curating a select class of people whose art we decided was the most important and charge people to come look at it, and then we in the art world look down on most people for not “getting” art.

i want a drawing space in every museum. hell, i want a drawing space in the gallery, right next to the van goghs and rembrandts and michelangelos. i want local artists to be uplifted by their community. i want museums to be engaging in conversations with native and indigenous groups, local activists and artists -- more than they already are -- and i want transparency from museums on the origins of their art objects & how they were acquired. i think there is a genuine fear that if we make art accessible to everyone, the capitalistic value of it will diminish, because no one wants to pay a lot of money for stuff that anyone can do. but a) obviously that’s flawed to begin with and capitalism sucks and b) people have a fundamental human right to participate in visual culture. people have a fundamental human right to creativity. people have a fundamental human right to art.

it’s not about teaching people how to be good artists, it’s about making it so people can freely participate in art-making without being traumatized away from it.

the high points for me during out of line were the moments when i’d see someone make the connection between drawing and themselves. the time i complimented a man’s drawing and then, quite visibly flustered, he hung it up and made all of his friends come and look at it. the time someone, after having drawn for a bit, told me they’d given up drawing as a kid but wanted to get back into it after drawing in the space. the group of older people who were hesitant until i explained to them how to do an automatic drawing -- arguably the one prompt of ours that required zero “skill” -- at which point they became so engrossed they stayed for hours, laughing and having fun, and so on. did any of them actually keep drawing at home? i don’t know. but if even for one moment, i could help provide a space where they could feel connected to drawing in their own way, then the whole exhibition was worth it.

thank you to deborah clemons, christina alderman, mariani lefas-tetenes, alexandra poterack and kajette solomon for taking me on and letting me play in your space. thank you to the risd museum security team for doing the work you do.

thank you to denise gunter for our insightful conversations on the space + museums in general, they helped me crystalise a lot of my thoughts in this zine!

citations

johnson, cathy g. “developing the cartooning mind: the history, theory, benefit and practice of comic books in visual arts education.” master’s thesis, rhode island school of design, 2017.

bayles, david & ted orland. art & fear: observations on the perils (and rewards) of artmaking. santa cruz: image continuum press, 1993.

malchiodi, cathy a. understanding children’s drawings. new york: the guilford press, 1998.

mignolo, walter. “museums in the colonial horizon of modernity” in globalization and contemporary art, edited by jonathan harris, 71-81. hoboken: blackwell publishing ltd, 2011.

further discussion of the art history canon can be found in drawing a dialogue, episode 10, co-hosted by myself and cathy g. johnson.